|

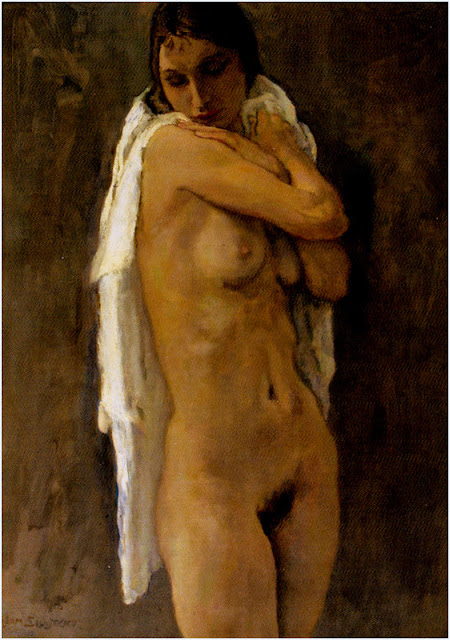

| Jan Sluijters (1881-1957), Standing Nude with White Drapery, 1935, Oil on Canvas, 45.7 by 32.3 in., Private Collection |

|

|

Still Life with Standing Nude, 1933, Oil on

Canvas, 55.1 by 45.7 in., Private Collection

|

|

|

Portrait of Greet Van Cooten,

the Artist’s Wife, Oil on Canvas, Dordrechts Museum, Netherlands

|

|

| Dr. Floren Marinus Wibauthuis (1859-1936), 1932, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam |

|

| N.H. ter Kuile and his wife, W.H. ter Kuile-Scholten, 1930, Oil on Canvas, 69.4 by 50 in., Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, Netherlands |

|

|

Half-Naked (wife of the

artist), ca. 1912, Oil on Canvas, 50.2 by 37.6 in.,

Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, Netherlands

|

|

| Adam and Eve, 1914-1916, Oil on Canvas, 69 by 79 in., Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, Netherlands |

|

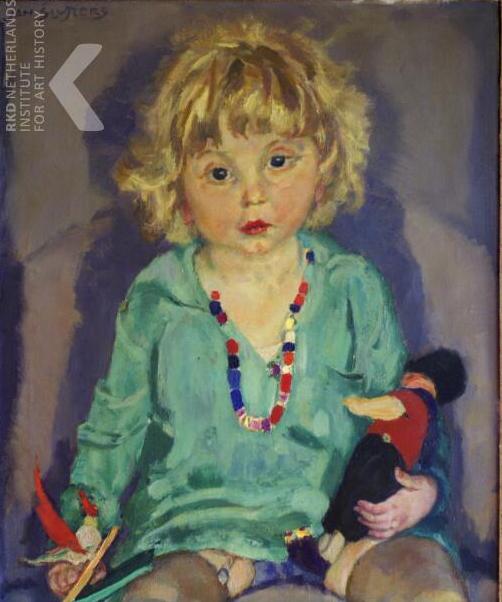

| Portrait of a girl, 1935, Oil on Canvas, 31.5 by 23.8 in., Private Collection |

|

| Portrait of Esther, 1940, Oil on Canvas, 23.6 by 19.7 in., Private Collection |

|

| Flowers in a White Vase, 1935, Oil on Canvas, 46 by 41.3 in., Private Collection |

|

| Standing Male Nude, 1904, Oil on Canvas, 35.4 by 23.6 in. |

|

| Seated Female Nude, Oil on Board |

|

| The Artist in his studio |

I instantly fell in love with the painting above titled Standing Nude with White Drapery when

I saw it in an auction catalog a couple of years ago. The artist’s sensitive, skillful depiction of

a woman’s body, in a pose completely free of artifice but sensual as can be, with

subdued natural light caressing the model’s lissome figure, was sublime. What a marvelous figure painting. I wanted desperately to paint that picture

myself. I had no desire to copy it, of

course. But I wanted to get the same evocative

feeling of ethereal feminine beauty in a nude figure painting of my own.

The graceful pose was perfect for this Dutch model with a Modigliani-like

figure. And oh, melancholy me, years ago

I knew a Dutch woman who resembled her very much. When I first saw this painting, I had been

drawing a model in the sketch group I frequent who had the same kind of figure

and emanated a similar statuesque serenity.

She would be ideal for my picture.

So this transcendent painting I envisioned was buzzing

around in my head for some time before I woke up and remembered who I was and realized

it was just another one of my many impossible dreams. It was, for want of a more probing disquisition,

hopeless. I’m nothing but an old painter

of modest still lifes -- mere bagatelles.

I have no money to hire models, no connections in the art world, and

lack the persuasive skills necessary to get people to pose for me for nothing,

as I may have already mentioned once or twice in previous musings. But it’s true and bears repeating until the

cows come home. Personal failures and

failings are a lot more fun to recount than successes any day, and doing so

always cheers me up.

Anyhow, creating large figure paintings in my tiny, jam-packed

home studio in a pre-war apartment building on Manhattan’s fashionable Upper West Side is

extremely challenging and nearly always unrewarding, despite some conciliatory words

from the sitters after they have been inconvenienced for a few hours, with

nothing much to show for their discomfort.

Not being able to paint my own version of this wonderful

painting was a huge disappointment at the time.

But the most important thing was that I now knew about this painting, and

it immediately found a place in my heart alongside all the other great

paintings I admire. I chanced upon it in

a Christie’s Amsterdam catalog published

for an auction of 20th Century Art in December of 1999 that I picked

up at a used bookstore in my neighborhood.

I suspect that the model for the painting was Greet Van Cooten (1885-1967). The painter was Greet’s husband, the

much-celebrated, somewhat controversial and hugely talented and prolific Dutch

painter Jan Sluitjers (1881-1957).

Greet was his second wife. Sluitjers won the Prix de Rome for an academic

painting he created while studying at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam in 1904 and married Bertha Langerhorst that year. They divorced in 1910 and he married Greet

in 1913. Sluijters was a very lucky man

to have a wife like Greet who would double as a steadfast, reliable model for

many of his figure paintings. And he got

a few paintings out of Bertha, as well, before they parted company. In addition, it seems that the quintessential

“model as mistress” theme was an important element in Sluijters’ artistic life.

Johannes Carolus

Bernardus (Jan) Sluijters (sometimes

spelled Sluyters) was particularly keen on painting nude figure studies of

women and portraits of women and girls of all ages and from all walks of life. A discerning retrospective exhibition of his

work at the Kunsthal in Rotterdam in 2003 was titled Women! Muse, Model and Lover.

Sluijters was a peripatetic modernist

who was comfortable working on the fringes of many of the post-impressionist

styles gaining favor with his contemporaries, but he never completely abandoned

his early academic training, always displaying some excellent drawing and sense

of traditional design in his stylistic adventures. He was considered a pioneer of various

post-impressionist movements in the Netherlands,

including fauvism and colorful expressionism. He also painted loads of landscapes

and still lifes, often in a loose, impressionistic manner. It seems he could paint anything he wanted in

any style he chose, with amazing skill. He

was free to do so because he had first learned how to paint and draw accurately

with the best of the academicians. His

later creative explorations must have seemed like child’s play to him. And it seems he never set his brushes down to

eat lunch or take a nap.

The exhibit in Rotterdam

displayed more than 100 paintings, prints and drawings of

his impressionistic, luminist, cubist and expressionist phases. It was said to give a pretty complete picture

of Sluijters' artistic development, from the book bindings and illustrations early on, through his brief but brilliant academic

painting years, and ending with the “colorful, lush paintings” he created from

about 1910 until his death 47 years later, at the age of 76. Some of his nudes scandalized the Dutch

public, with one reviewer comparing the women to “vampires.” His portrait of a woman with a big grin and

huge red lips caused another reviewer to remark, “Her

red mouth is the forbidden fruit.”

When I started to look for his work

on the Internet, I was absolutely blown away by the enormity of his recorded

output, particularly in evidence on the RKD Netherlands Imagebase, which

displays 2,048 images of his artwork on 41 pages of a digital catalogue

compiled over many years of research.

What an immense task. After about

10 pages of 50 images each, I was worn out and abandoned my search to find the

perfect paintings to illustrate this blog post. I gather that most of his artwork is in

private collections or museums in Europe.

Every one of his works has

something interesting to offer for any serious art lover. What an imaginative figurative artist he was.

Everything seemed to interest his nimble artistic mind, not just the female

form divine. He seemed to float lightly

across the entire post-impressionist landscape, producing gems wherever he landed.

Someone at the RKD Netherlands

Imagebase wrote that Sluijters was

a painter through and through. With vigorous

movements of the brush and a palette of bright and sharply contrasting colours he immortalized beautiful women, sweet children, sundrenched landscapes

and exuberant flower still lives on his

canvases. Sluijters began his

career as an experimenter, trying out

practically every ‘-ism’ of his time. In the course of his

life he gradually toned down his style to a more moderate but highly successful

combination of expressionism and realism. Working steadily he produced no fewer than 1500

paintings.

Sluijters was nicknamed the “painter-beast” by his

contemporaries because of his rugged, robust appearance and insatiable appetite

for painting. He was no dreamer.