|

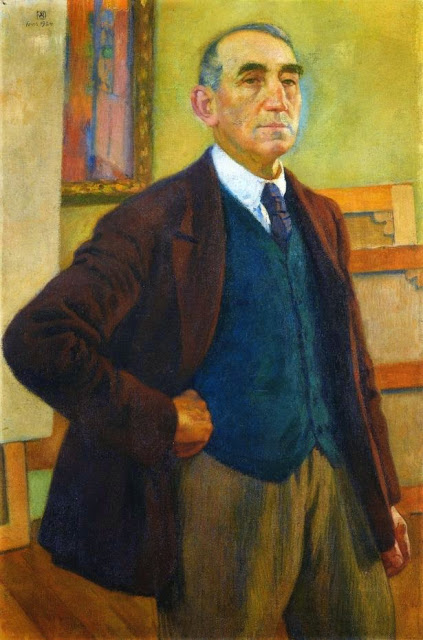

| Theo van Rysselberghe, (1862-1926), Self Portrait, 1924, Oil on Canvas, 45.4 by 30.25 in., Private collection |

|

| Theo, Portrait of Alice Sethe, 1888, Oil on Canvas, 194 by 96.5 in., Musée partemental du Prieuré, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France |

|

| Theo, Madame Von Bodenhausen with her daughter Luli, 1910, Oil on Canvas, 46 by 37 1/8 in., Private Collection |

|

| Theo, Jeune femme en robe verte (Germaine Maréchal), Oil on Canvas, 32 1/8 by 23 7/8 in., 1893, Private Collection |

.jpg) |

| Theo, La Vallee de la Sambre, 1890, Oil on Canvas, 21 1/8 by 26 1/4 in., Private Collection |

|

|

Theo, Emile Verhaeren, 1915, Oil on Canvas, 30.3 by 36.2

in., Musée d'Orsay, Paris

|

|

|

Theo, Emile Verhaeren Writing, 1915, Oil on Canvas, 35.8 by 40

in., Private Collection

|

|

| Theo, Standing Nude, 1919, Oil on Canvas , 39.4 by 25.8 in., Private Collection |

|

| Theo, Study of Female Nude

Etude de femme nue, 1913

, 1913, Oil on Canvas, 25.8 by 39.4 in., Musee d"OrsayOil on canvas, 65.5 x 100 cm Musée d'Orsay - See more at: http://impressionistsgallery.co.uk.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/artists/Artists/pqrs/Rysselberghe/07-14.html#sthash.Ld4fZKFS.dpuf |

|

| Theo, Swimmer Resting, 1922, Oil on Canvas, 36.2 by 43.7 in., Private Collection |

|

| Theo, A Reading in the Garden, 1902 |

|

|

: Theo, Paul Signac (at the

helm of the Olympia), 1896, Oil on

Canvas, Private Collection

|

|

| Theo, Still Life with Khaki, Roses and Mimosas, Oil on Canvas, 1911 |

So many great paintings of his are recorded on the Internet that it’s hard to stop when you start downloading. Let’s say you admire Theo’s very entertaining and beautifully crafted painting of his friend, the Belgian Symbolist poet and writer Emile Verhaeren, showing him with his head buried in his work, his superbly drawn hands artfully posed to characterize the task of writing. The design of the canvas is a masterpiece of balance, with related elements strategically placed to take the viewer on a casual cruise around the laboring poet’s domain. Then you follow another link and up pops a full-blown portrait of the striking Verhaeren at the same desk, now with his head out of the water. This one begs for attention as well. What a dilemma van Rysselberghe poses for the lover of fine painting. Rev up your search engines and see for yourself. You won’t be disappointed.

Théo (Théophile) van Rysselberghe (1862-1926) worked expertly and comfortably in all genres and in several styles within the broad rubric of Realism, beginning with classical or academic work at the age of 18, moving on to Neo-Impressionism, then to Pointillism, the approach that earned him his lasting reputation in the world of art, and finally back to working realistically in an Impressionist manner.

Van Rysselberghe was born into an upper middle class family of architects in Ghent. He studied art at the Academy of Ghent and at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. In his formative Realist years, he spent four months in Morocco in 1882 to paint scenes from that exotic Orientalist culture. Between 1882 and 1888 he made three painting trips to Morocco. The public loved his Moroccan paintings.

In September 1883, van Rysselberghe went to Haarlem to study the light in the works of Frans Hals. “The accurate rendering of light would continue to occupy his mind” all his life, wrote an online biographer. By way of illustration, in 1918 he painted a picture of blossoming almond trees over a period of 15 consecutive days, returning to the scene at the same time each day to get the impression of light and atmosphere as close to nature as he could. The painting, Amandiers, à contre-jour (backlighting), was sold at auction by Bonhams on Feb. 4, 2014. While no doubt a fabulous painting viewed in person, its image doesn’t look great on my computer screen so I didn’t download it. Bonhams wrote that the painting of almond tree blossoms in the small village of Saint-Clair in southeastern France “proved to be the perfect setting, with the dappled sunlight filtering through the delicate blooms, to demonstrate his enduring interest in rendering light and colour.”

For some reason, van Rysselberghe had to write to Madame Lucien Pissarro to ask for permission to paint those almond trees. Maybe it was her property? It would be interesting to know why, but I’m way over budget already on this blog post. Van Rysselberghe wrote, “'I hope you would not withhold against me... if I ask for the permission to go to Saint-Clair around three o'clock, in order to have a session with my almond trees, which are finally blossoming, and for which I cannot bare to lose a day where the effect will not be more or less the same.”' The letter is quoted in Ronald Feltkamp’s 2003 catalogue raisonne on the artist.

Some 30 years before he painted those almond blossoms, the young van Rysselberghe became fascinated by the newest tendencies in European art and embraced the theories of the Neo-Impressionists. He fell under the spell of Pointillism when he saw Georges Seurat's large-scale work, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-1886), at the eighth Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1886.

After meeting and becoming friends with Seurat, Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross, van Rysselberghe began to put those small dots of color on his own canvases. Van Rysselberghe was a better painter than the other Pointillists and a terrific portrait artist as well, which seems impossible using such disciplined brushwork. He remained faithful to his own realistic interpretation of nature through all his stylistic adventures, gradually abandoning the Pointillist technique after Seurat’s death in 1891. Despite their friendship, Signac often criticized him, thinking that Theo was only interested in commercial success when he began adapting the broadened brushstrokes of Impressionism, ostensibly to appeal to a greater public.

Theo had fully embraced Pointillism by 1889, according to his biographers. But a year earlier, at the age of 26, he painted one of the most remarkable paintings ever, a 16-foot-tall portrait of a model, using nothing but small dots of color to complete the work. I couldn’t believe the size of this painting when I asked my Internet confidant to convert centimeters to inches. I had to double-check the online conversion to see if it was correct. What a time-consuming task that must have been! I mean creating the painting, of course, not the conversion from centimeters to inches, although I was put out to have to interrupt my research to consult with my steadfast online confidant a second time.

This giant portrait of Alice Sèthe, in blue and gold, became the turning point in van Rysselberghe’s life. He went on to create scads of normal-sized portraits, figures, landscapes and still lifes in the Pointillist technique. Among his portraits were several of his wife, Marie Monnom, whom he had married in 1889, and many of their daughter Elisabeth. The Belgian symbolist painter Fernand Khnopff painted a famous portrait of Marie in 1887 that is now in the Musee d’Orsay. She was the daughter of an avant-garde Belgian publisher, Veuve Monnom (the Widow Monnom). The Widow Monnom knew many artists and writers and is described as one of many little-known female modernists in the late 19th Century.

Around the time of his marriage to Marie, Theo van Rysselberghe had a meeting with Theo Van Gogh in Paris, which led to Vincent Van Gogh’s sale of The Red Vineyard to the Belgian painter Anna Boch from an exhibition in Brussels, the only confirmed sale of one of Vincent’s paintings during his lifetime. Anna Boch participated in the Neo-Impressionist movement and was influenced by van Rysselberghe. Boch held one of the most important collections of Impressionist paintings of its time and promoted many young artists, including van Gogh, whom she admired for his talent and who was a friend of her brother Eugène Boch. Her collection was sold after her death with the stipulation that the money be used to pay for the retirement of her poor artist friends. What a lovely gesture and what a good heart she must have had. Van Rysselberghe painted an excellent three-quarter-length standing portrait of her in 1893 that is now in the Michele & Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts in Springfield, Massachusetts.

After abandoning Pointillism, from about 1910 on, van Rysselberghe worked in an Impressionist manner directly from nature. He experimented occasionally with more vibrant color combinations in some of his paintings. He also added the painting of nude female models to his dessert menu – a pleasant diversion for many celebrated male artists of yore in their mature years. And why not? Nothing is more thrilling than capturing the essence of youthful flesh on canvas, which he accomplished to perfection.

When his Pointillist years were nearing their end, Theo took a bike tour of the Mediterranean coast between Hyères and Monaco with his friend Henri Cross. Theo found an interesting spot in Saint-Clair, where his brother, the architect Octave van Rysselberghe, and Cross already resided. Octave built a residence for him there in 1911 and Theo retired to the Côte d'Azur and became more and more detached from the Brussels art scene. He died in Saint-Clair on December 14, 1926 and was buried in the cemetery of nearby Lavandou, next to the grave of Henri Cross.

Many of Van Rysselberghe’s paintings that were so enthusiastically acquired by private collectors in his lifetime have ended up on the auction block, including one of the first paintings of his that won my heart, his enchanting portrait of Madame Von Bodenhausen with her daughter Luli, which he painted in 1910. One of Madame’s children was cut out of this portrait for some reason that eluded me in my Internet research. Sotheby’s writes that Luli grew up to be a great beauty and star, using the stage name Luli Deste after she moved to Hollywood. She starred in a number of movies, including Thunder in the City with Edward G. Robinson in 1937. I haven’t seen the movie. I’m sure Sotheby’s is right and I have no desire to look further into Luli’s Hollywood career. Painting pictures is more than enough cinema for me these days. At any rate, this gorgeous painting of mother and child sold at Sotheby's London on Feb. 4 of this year for a mere $28,436, after failing to sell at a previous auction.

Meanwhile van Rysselberghe’s Pointillist portrait of a rather glum-looking Germaine Maréchal, titled Jeune femme en Robe Verte, which he painted in 1893, had sold for $1,223,108 just five years earlier, on Feb. 2, 2010 at Christie’s London. Did Theo’s stock decline so rapidly in the art world in just five years? Or did Christie’s simply have a better salesman on the case? Maybe it’s because the portrait of Germaine is such a perfect example of his Pointillist phase. Maybe it’s because one of Madame’s children was lopped off in that portrait. As usual, I’m clueless. It’s easy to put a price on a painting, but it’s impossible to know for certain what it's worth in the marketplace. I know that for certain.