|

|

Sir William Orpen (1878–1931), Self-Portrait, Leading the Life

in the West, ca. 1910, Oil on Canvas, 40

1/8 by 33 1/8 in., Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

|

| William Orpen, Self-Portrait with

Sowing New Seed, 1913, Oil on Canvas, 48 3/8 by 35 3/8 in., St. Louis (Missouri) Art

Museum | | | |

|

| Portrait Photographs, National Portrait Gallery, London |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| William Orpen Sketches: Pleading with Sargent, Slugged by Yvonne Aubicq, Army Examination, Suffering from Blood Poisoning |

|

| William Orpen, Mrs.Evelyn St. George, 1912, Oil on Canvas, 85 by 47

in., Private Collection |

|

|

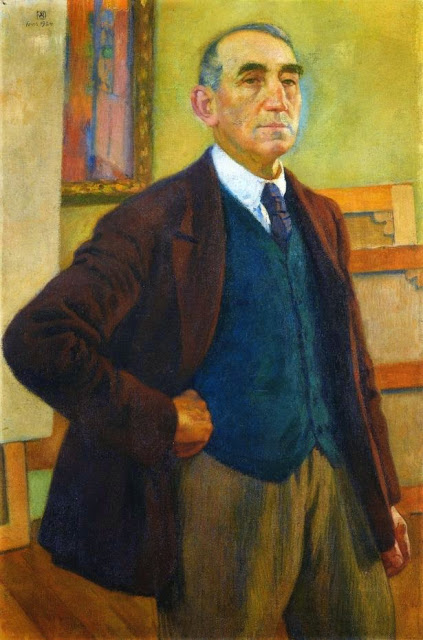

James

Sinton Sleator (1885–1950), Portrait of Sir William Orpen, 1916, Oil on

Canvas, 38.11 by 36.14 in., Crawford

Art Gallery,

Cork, Ireland

|

|

|

Fats Waller (1904-1943),

www.morethings.com

|

I read a story some years ago in a New

York tabloid about a little kid from South

Africa who was afflicted with progeria, that

rare genetic disorder where kids age prematurely and die young. At the age of 10, the poor kids who suffer

from this disorder have stunted growth, look like 70 and really stand out in a

crowd. At the end of this article, the

kid asks his mother why he looks so different from all the other kids. His mother tries to comfort him by telling

him that he is “special.” But the little

kid replies, “It’s not nice to be the only one.”

I cried my eyes out when I read that story, mostly for the

little kid’s misery, but also for myself a little bit, too. I’ve always felt that I was the only one in

the crowd who was different. Most

introverts feel that way, I suppose. But

because your state of mind and corporeal identity are what matter most to you,

everything is relative, and it’s hard to erase that feeling of being one of a

kind and all alone in this world.

I developed a sense of deep melancholy early on that has

lasted all my life. I often think I

should just throw myself in front of an oncoming subway train or bus, jump in the

Hudson River, or turn on the gas jets some night – the usual things, I’m not

very creative.

My preferred rite of departure would be to just lie down in

a snow bank and go to sleep, like Per Hansa in Ole Rolvaag’s “Giants in the

Earth,” a dismal novel about Norwegian pioneers in the Dakota Territory. One winter Per goes to find help for his

family, gets caught in a blizzard and freezes to death. But New York City

is not in prairie country and very seldom gets blizzards or snowstorms. When it does, the snow banks don’t last long

enough to serve as a proper burial ground.

Per’s lasted until the spring thaw.

I can’t seem to convince my tribe’s medicine men to certify

me and load me down with happy pills to alleviate my transitory bouts of

depression. And I always erase my darkest thoughts with the chilling

introspection that I’ll die soon enough anyway.

I made it through grade school and high school without

experiencing too many horribly embarrassing moments. And those were usually the result of my own

foolishness, an incurable disease if ever there was one. There always seemed to be one or two other

kids who were easier targets for the class jokers. Besides, the wiseguys and practical jokers were

quite scarce in my little farming community on the prairie in the middle of nowhere

corn country. Most of my classmates were

farm kids who worked too hard to waste time figuring out how to humiliate each

other. Of course, you can’t avoid

hearing things people say about you that sting a lot more than sticks and

stones. Are you listening up there, Ma? And then in college and the army you really

get to see yourself as others see you, and you are too mortified to seek a

second opinion. But life goes on and you

find ways to cope with your neuroses, at least if you aren’t really as crazy as

you think you are. Now I know that depression can be devastating and is no

laughing matter for a lot of people, but that’s what works for me.

In my early 30s, I left the real world behind to study

drawing and painting in an art school.

All of a sudden I was surrounded by lots of other people who seemed to

be like me in many ways, perhaps also harboring some secret hurt that prevented

us from living the “American Dream” in the suburbs, with a wife and kids, a

two-car garage, a good-paying job, seasonal sightseeing vacations, skiing trips

in the winter and barbecues on the backyard patio in the summer to break the

monotony. Isn’t that how it goes?

All of a sudden I had finally found something to occupy my

time that was so much more important than spending years on an analyst’s couch

trying to pump up my self-esteem. All of a sudden I was having downright fun

for the first time in my life. Thoughts

of leading a normal life like most other people no longer consumed me. Of course I have no idea how other people

really live. But I’ve heard rumors.

Painting religiously turned out to be the best therapy for all

those times I was made to feel miserable by certain comments delivered by mean

or insensitive people or by having to fulfill all those cringe-provoking social

obligations along the way that I wasn’t clever enough to avoid, like Junior and

Senior Prom Nights. And that Sadie

Hawkins Day dance. Lord have mercy!

The great Irish painter William Orpen, whose God-given

talent for capturing likenesses earned him a fortune, knew something about

depression. And like me, he was the

youngest of four sons. That’s not the

most enviable rung on the family ladder, in my long-held and well-considered

opinion.

Major Sir William Newenham Montague Orpen, KBE, RA, RHA (27 November 1878 – 29 September 1931) was born in

Stillorgan, County Dublin

into an affluent Protestant family. His

father was a lawyer who wanted his youngest son to study law and enter the

family firm. But Sir William had a

talent for drawing and his mother supported his desire to go to art school. And mother always knows best, doesn’t she?

Orpen was small in stature, just over 5 feet tall, and

self-conscious about his appearance his entire life. He had a very miserable childhood, by his own

account.

In a 1924 memoir, Orpen writes, “My general appearance, and

especially my face, have always been a source of depression to me, even from my

early days. I remember once, by mistake,

overhearing a conversation between my father and mother about my looks – why

was it I was so ugly and the rest of the children so good looking … I remember

creeping away and worrying a lot about the matter. I began to think I was a black spot on the

earth and when I met people on the country roads I always used to cross to the other

side.”

Despite overhearing this devastating conversation, which

precipitated his lifelong depression, Orpen is said to have doted on his mother

until she passed away in 1912, leaving him disconsolate for a time.

The art world of the early 20th Century didn’t care about Orpen’s

depression. It cared about his art. He won all the honors and all the accolades

and attracted all the cash anybody would ever want. One reviewer called him “the last of the

great society painters.” By the start of

World War One, Orpen was the most famous and commercially successful artist

working in Britain. John Singer Sargent, who was easing out of

the portrait business at the time, promoted Orpen’s work, which was more daring

than that of his rivals. He often lit

his figures from two sides, giving his portraits a luminous quality and a dramatic,

almost cinematic look that is highly effective.

But it’s not a technique that is easy to master, as I have discovered. It’s hard enough to paint a decent portrait using

just one light source.

Orpen married Grace Knewstub in 1901, and the couple had

three daughters. But it was an unhappy marriage, and despite his self-loathing, Orpen was a determined

heterosexual who manfully entered into affairs with many women, sometimes more

than one at a time. The British website “Articles and Texticles” provides a

pretty thorough account of Orpen’s intimate relationships. He had affairs with many of his models. He

kept a French mistress, the beautiful, feisty Yvonne Aubicq, an affair that

provided enough plotlines for a novel. Most

importantly for his career, he had a celebrated affair with Mrs. Evelyn St George,

the London-based eldest daughter of George F. Baker, a filthy rich American

banker.

Eight years older than Orpen, Mrs. St George had grown tired

of her husband and is said to have had numerous extramarital flings. The humorous turn of phrase, “No sex please,

we’re British,” hardly applied to these two.

(Yes, I know, one was Irish and the other American, but they were in London

at the time. Give me a break once in

awhile.) When the diminutive Orpen and Mrs.

St George, who was over 6 feet tall, appeared in public, as they frequently did,

they became known as “Jack and the beanstalk.”

They had a “lively and adventurous love affair,” according to one Irish

newspaper account. And Orpen was the

father of Mrs. St. George’s youngest child, Vivien.

“Evelyn St George was undoubtedly the most important person

in William Orpen's life,” wrote a reviewer in Dublin’s

Irish Independent in 2001. “She gave him

happiness and she gave him love. She inspired him as an artist. She told him

what a great painter should do, what sort of pictures he should paint, how he

should view the world and how he should address it.”

Orpen’s frenzied extramarital activities were probably great

fun at the time, but depression and all the sex destroyed him. He became an alcoholic and died a lingering

death from syphilis in 1931 at the age of 53, thus depriving the art world of

maybe 20 more years of his dazzling portraiture.

At the outset of this disease it wasn’t given its name. A doctor who examined him during his years as

a WWI artist concluded that Orpen was suffering from “blood poisoning,” after

other health workers had attributed his severe bouts of itching first to lice

infestation and then to scabies. He candidly

describes suffering recurring bouts of this “blood poisoning” during the war

years in “An Onlooker in France

1917-1919.” This fascinating personal account

of his painting activities and life during the war, with many black and white

reproductions of his artwork, is available for reading online or

downloading. After the war, Orpen

continued to paint outstanding commissioned portraits before falling ill and finally

dying from this awful disease.

In a review of the exhibit, William Orpen, Sex, Politics and

Death, at the Imperial War

Museum in London

in 2005, Berendina “Bunny” Smedley writes,

“…it seems fair to say that compared with politics and death, sex was a topic

that appealed to Orpen. Probably he discovered it early at art school, and then

effectively forgot it again in his grim last years, when, as syphilis took its

toll, his relationships both with his wife and mistresses fell badly apart. Sex

was there, often, in his pictures, sometimes very evidently so.

“Not for Orpen the icy academic nude, the female form as an

exercise in mass and contour, [an] ironic art-historical allusion. Orpen really

did love women, not as abstractions, either, but for all their physicality and

flaws. And if it’s true, as suggested earlier, that his paintings of men were

often better than his paintings of women, the reason may lie less in misogyny

and objectivisation than in tact, kindness and the hope of an earthly reward

for his efforts.

“There are paintings here that read like love-letters,

albeit those of the most delightfully flippant, non-serious sort and they form

one of the most attractive aspects of Orpen’s oeuvre.”

What a brilliant and incredibly perceptive analysis of

Orpen’s love for women and his paintings of them – whether depicted in the

nude, in a washerwoman’s clothes, in a nun’s habit worn by his French mistress,

or in the elegant, floor-length gowns worn by the tall, beautiful women he

adored and chased after. As Smedley

described far more eloquently than I can, Orpen’s paintings are not flawless academic

renderings or empty society portraits.

They are simply mesmerizing images of the opposite sex – nothing less

and a whole lot more.

“It is my business in life to study faces,” Orpen once

said. “It is also my lot in doing my job

to get to know automatically what is in the mind that is behind the face, and I

do not hesitate to say that there is no such thing as real beauty of face

without beauty of mind. And there is a lot of both kinds of beauty today.”

For someone as disgusted with his own appearance as he

claimed to be, Orpen painted a surprising number of self-portraits in oil on

canvas and drew countless cartoon images of himself on letters to his friends. They were all exaggerations of his physical

appearance and often savage caricatures.

Painting was Orpen’s salvation, women his fatal attraction

and alcohol his escape mechanism. The excellent Irish painter Sean Keating, a friend

and former studio assistant to Orpen, called him a "two bottles of whisky

a day man"

In the midst of composing this blog post, I watched a

YouTube video called “Fats Waller, the Very Best,” uploaded by a poster named

Ugaccio. Near the end of the video, Fats

is on camera singing his big hit “Ain’t Misbehavin’ when an unidentified male

voice comes on to speak about him. The unseen

commentator concludes with words that could just as easily have described Sir

William Orpen: “He lived in a fast

lane…He dissipated a lot, drank a lot…Takes a toll after awhile…People with a

whole lot of talent don’t usually live very long. They’re here, they do their thing and get

outta here.”

I don’t know if Thomas Wright “Fats” Waller was depressed. I think he was too active for introspection

during his brief life. But he was a

large man, with a very distinctive appearance.

He had a massive head, a massive girth and a massive appetite. He was 6 ft. tall and weighed in at nearly 300

pounds. He died of pneumonia in 1943 at

the age of 39. Sir William Orpen, called

“Orps” by his friends, was an undersized man, very scrawny in his younger

days. He outlasted Fats by 13 years on

this earthly paradise before leaving his noteworthy legacy to the world.

Hearth and home and the simple pleasures of life enjoyed by most

so-called normal people were not meant for these two supremely talented artists.

They were too “special” for any of that

humdrum sort of stuff.

.jpg)